One of my greatest wishes for the Bliss Habits blog is that the topics to be of interest and the queries and conclusions you discover make a difference in your life. I’m truly honored and delighted that this has been the case for my dear friend Kat. Long time readers may remember Kat tackling difficult topics here before; Birthing creativity from loss and Indefinite Detention, today she gets to the heart of being naked and the types of armor we use to hide. Follow her journey and discover your own.

I write this for my brother Michael Neil Dean. And for an actor I have always had tremendous respect for, Philip Seymour Hoffman. And I write this for me.

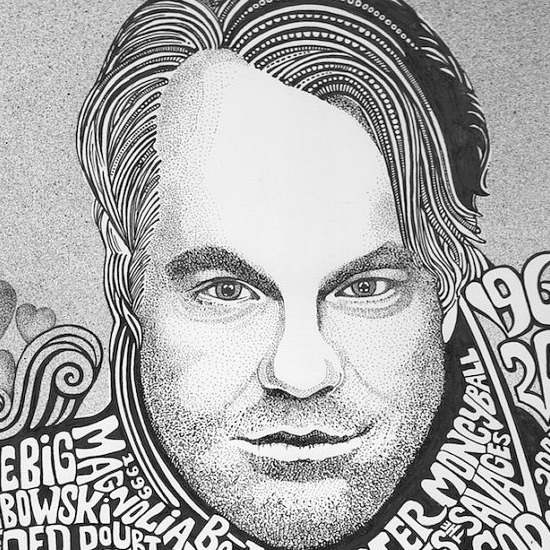

by Ben of “Posterography”

I am deeply saddened by the death of Philip Seymour Hoffman. This is in part because Hoffman reminds me of my youngest brother Michael, who at twenty-one, died of a deliberate overdose, almost three decades ago. Hoffman physically resembled my brother, who was solidly built, with a comfortable, some might say rumpled manner of dress. They also shared a similar expression when photographed. Hoffman had kind eyes, but they revealed an undercurrent of sadness, that my brother also revealed in almost every picture taken of him, close to the time of his death. So with Hoffman’s passing, my brother’s suicide revisited me.

But the other reason I am devastated by Hoffman’s fatal descent into drugs is that I identify with his struggle to keep the demons at bay. I too battle addiction. And every time Bliss Habits explores the topic of being naked, it brings to mind just how naked I have always felt in the world, and of all the armor I attempt to don in an effort to feel safe and at ease, when I otherwise live in a constant state of muted terror.

One point Hoffman made when interviewed about his own struggle, was that there isn’t just one source for addiction—as in, if you are an addict, you might choose to hoard, or drink, or shoot-up—but the stuff you use to quell the beast within, isn’t really the essential thing. The core of an addiction is not as tangible as the method of the addiction. It’s like a cough—you feel the impulse to release it, but never quite understand how, why or where it originates from. Which is why addiction can be so difficult to conquer. You can cease drinking, only to find you’ve transferred what the alcohol did for you to some other obsession.

I am not partial to most drugs, but wine is just fine. And I also hoard, eat more than I should, watch way too much television, play solitary computer Scrabble and Monopoly like they were heroin. When I’m in a good place in my life, all the above are indulged in, for the most part, with a degree of moderation. OK, maybe not the wine. But when things go wrong or sometimes even when they go right, or when I’m feeling particularly naked, I can dive into an armor of oblivion so immense and fortified, it is as if I were a medieval knight preparing for battle. And it is a very heavy coat of armor that I wear.

Philip Seymour Hoffman was found with the heroin needle still in his arm. I ponder as to how I might be found if I collapsed in the middle of one of my binges.

I imagine I would be discovered slumped over my computer, probably attempting to buy Park Place. There would be a mimosa to one side, guac and chips to the other. And the TV would be on, blaring a Law & Order marathon. It’s a complete sensory annihilation-blitz worthy of a really bad Lifetime, television-for-women, movie (movies I also love to binge to).

I have to, and do, laugh at the absurdity of my own actions. I’m not a dumb broad. I know better, really, then to lose myself in this nonsense. But some part of me doesn’t care. And I also know that beneath this seemingly benign laundry list of quirky dependencies, I feel especially exposed to the world, and extremely susceptible to what is harsh around me (even though I appear tough), and I am sad in ways that are very difficult for me to communicate to anyone.

And this is very much how my brother ended his life. He’d rented six films the day of his death. Two that were notable to me were The Wizard of Oz and 2001: A Space Odyssey. Which always seemed fitting, given our intellectual, yet escapist family. I don’t know, but I believe he watched all six films that day, in his rented room in the Height Ashbury neighborhood of San Francisco, and drank his beer and popped his anti-depressants, which he had stock-piled—most likely for this purpose. He had two full bottles of Elavil at the ready.

Then he did something I wouldn’t have, even if I were to end things—he took a blanket from his bed and walked from his rented room to Golden Gate Park, which was only a few blocks away. He hid amidst thick foliage near a small lake, and he folded himself into his blanket and died. A week later a jogger discovered him. It was clear from his actions that my brother had not wanted anyone to stop him. His suicide note began with: “This world is meant for you not for me,” and ended in: “Fuck ‘em if they can’t take a joke.” But the note was addressed to no one in particular, or perhaps to everyone in general. It was a poignant and sad end to what had been a troubled life.

Though I have never been close to doing what Michael did, my patterns resemble his, and so what seems benign on the surface, feels serious to me as well. But I’ve never given it the effort my brother did.

In a way, I respect Hoffman’s determination, as well. Both my brother and Hoffman’s commitment to their self-destruction had a certain discipline to it, as well as abandon. But the benefit of being a bit of a pussy at binging is that my chances of coming back from the abyss are perhaps greater. The danger is that I might not make the changes I need to make, because it is easy to shove the idea aside that change is even required. I don’t shoot heroin. I’ve never attempted suicide, so I must be OK.

The truth is that even if I’m not shooting up, my methods of release can damage me. It’s never just one mimosa that I drink, or one game of solitary Monopoly I play to numb my mind, or one episode of Law & Order watched—it’s many. And many more after that. And maybe just a few more after that. Or maybe it’s a day of….or a week of…or a life of….

And that’s when an indulgence, which might wear like a warm and fuzzy sweater in small doses, becomes a heavy armor, an encumbrance rather than a shield—something I label as addiction, but don’t really know well enough to cure in full. No one has. And that again is where Hoffman’s death was upsetting.

I had always believed that if only my brother had survived his twenties, he would have discovered that is possible to get past the bad days. They don’t last forever. Hoffman even said something to this affect in an interview soon after he left rehab for the last time. But it’s not true that age factors in. The: this-bad-day-may-never-end-syndrome, can hit at any point in life. And this is a discouraging and painful discovery, if you live it.

For me, my really bad day began with menopause, which coincided with a career I’d nurtured and treasured, having suddenly vanished. I fell under a deluge of uncertainty, blind-sided by unforeseen events—hormone madness from within, huge new challenges facing me at my front door. And bad choices that followed. My really bad day lasted for almost a decade.

I’d always battled depression, but for the first time depression truly had the upper hand. And so I succumbed to my odd, seemingly banal addictions. They’d always been there lurking. I’d felt their presence my entire life, but now that I had lost my balance, they pounced, as if they weren’t a part of me at all, but some malevolent force hidden in the recesses of my being, that had impatiently waited, hoping for the day I’d lose my footing. And that day had at last arrived—hurrah.

Fortunately, or not, I like being here too much to leave. There is always something to live for, even if it is self-destruction, and my very bad day did eventually subside. Menopause ended. I remember about a year ago suddenly feeling my body relax into a new place it had nearly torn me to pieces to be in. I’ve embarked on a career that fascinates me. And even though I’m only on the brink of it, what I had craved all along was a new purpose, an endeavor that excited me again, and I’ve found this. I am home again in my body and in my life. And I’ve made some significant changes in where and how I live that are already bringing me a lot of joy.

But there still is, as Neil Young so eloquently sings, “the needle and the damage done”.

Addiction is a leach. It is habit. It’s all the things that are difficult to pull one self out of because they become as natural and reliable as breathing. It’s a process that takes time, and the most important part of this process, I have learned, is to take the time. But ironically there is another important component to recovery I’ve found. It is in the very thing I run from when I choose oblivion over life—it is my naked self. In the ability to live naked, which to me means to own every single aspect of who I am—all that is despicable and all that is glorious—in accepting it all, there is a different type of garment I shrug into, different from the rigid articles of steel once used, this cloak is supple and rather than weighing me down, moves with me.

Studies have shown that the heavy armor worn by medieval knights may have hindered victory, as the energy required to move within bulky steel sapped the strength of fighters as they went into battle. I’ve come to understand that being naked isn’t my most vulnerable state, because my strength never really came from a hard exterior, as I had always supposed. Naked-me is able to move quickly and with ease, to bend, and to yield when necessary. Naked-me is actually better equipped to take on all of the challenges I face from outside and within, because losing the heavy coat of armor, I gain momentum.

This discovery for me isn’t a cure-all. I am in a constant dance with my demons—and they know the steps to the dance, just a little better than I do. Depression and suicide run in my family. What I’ve battled, I may always battle. But it’s nice to remember that even as I lose, I also win. And that, that nightmare where I find myself walking a busy street without a stitch of clothing on, can under the right lens, turn into a state worth sustaining.

Hoffman inspired me. He appeared to have grasped the holy grail of sobriety. He was not only sober, but he did “sober” with flair. And he did it openly, honestly and successfully for a very long time. His victory was a gift for anyone struggling with addiction. True also, is that he lost the battle. And this is upsetting and tragic. Just as it will always be tragic for me that my brother Michael left the game before his turn was really up.

But part of accepting who I am naked, is that in viewing the ugly, I don’t shame what is beautiful. Hoffman’s successes are every bit as significant as his failure, and for me his victories are more so. It’s all part of the same thing. And embracing it in full may not solve life’s impenetrable dilemmas, but it makes for a better time while I am here.

And that is the real gift I have been given. I am here, now. And when things are good, it’s more than enough. And when things are bad, I try hard to remember that the pendulum always returns—the good stuff is as definite as the bad. There will always be both, and the good is worth fighting for.

*************

I was born in 1961 in Northern California. Spent my formative years growing up in San Francisco, in the ‘60s and ‘70s. I moved to New York City in the early ‘80s to dance, and after a number of years being completely broke in that pursuit I fell into the Music Industry, working in production for almost twenty years.

I was born in 1961 in Northern California. Spent my formative years growing up in San Francisco, in the ‘60s and ‘70s. I moved to New York City in the early ‘80s to dance, and after a number of years being completely broke in that pursuit I fell into the Music Industry, working in production for almost twenty years.

Around 2001 there was change in the industry, away from recording the bulk of a project in a large facility to recording almost the entire project in a home studio.

I recently completed my paralegal certification at Georgetown University. My new home in Alameda, California affords me great joy. Everything in my life is new right now, but with three collies in tow, there is a ton of puppy love.

What a powerful piece of writing – I felt everything you say deep in my heart! I identify with so much of what you say – the armour that holds everything out, the sensory overload – and until now hadn’t even considered any of it as addiction! Your story nearly brought me to tears – of sorrow and of joy for the hope and strength you display. Thank you xxx

Karen, that means so much to me. Thank you!